Bitter Winter 2 Settembre 2023

Bitter Winter 2 Settembre 2023

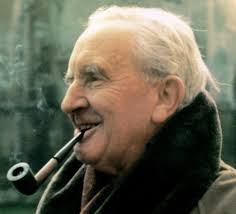

The great English writer died on September 2, 1973. An important testimony emerges from an unpublished letter of January 1969.

by Marco Respinti

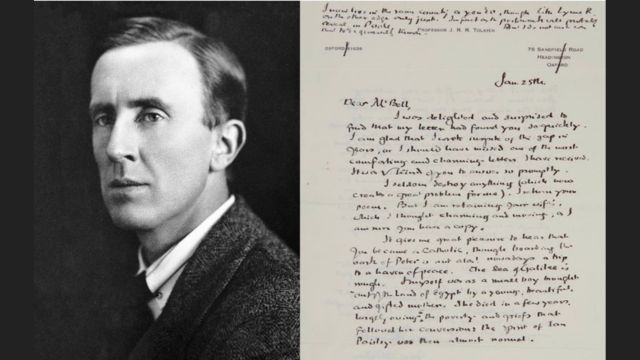

While meditating on “the catholicity of the Reformation” from what I apprehended through history and conversations in the town of Bergerac, France, I came across an unpublished letter by English author and philologist J.R.R. Tolkien (1892–1973). My attention to its content was captured by both its relevance for the “Mere Christianity” theme, that I dealt with in previous “Bitter Winter” articles, and my personal intellectual curiosity, being the translator of the Italian edition of Tolkien’s 1976 “Letter from Father Christmas” and the revisor of the translation of his 1977 “The Silmarillion,” as well as the co-author of a book on Tolkien’s Roman Catholic faith.

A rich selection of Tolkien’s correspondence was published in 1981, edited by English biographer Humphrey Carpenter (1946–2005) and the author’s son and philologist Christopher J.R. Tolkien (1924–2020), but of course many other letters exist. Some letters sometimes find their way to auction houses, for the delight of wealthy collectors. A letter by Tolkien dated January 25, 1969, and sent to his friend Michael Bell from Poole (a coastal town in nowadays Bournemouth, Christchurch and Poole unitary authority area in county Dorset, England), was recently auctioned by Christie’s in London, the largest auction house in the world.

A rich selection of Tolkien’s correspondence was published in 1981, edited by English biographer Humphrey Carpenter (1946–2005) and the author’s son and philologist Christopher J.R. Tolkien (1924–2020), but of course many other letters exist. Some letters sometimes find their way to auction houses, for the delight of wealthy collectors. A letter by Tolkien dated January 25, 1969, and sent to his friend Michael Bell from Poole (a coastal town in nowadays Bournemouth, Christchurch and Poole unitary authority area in county Dorset, England), was recently auctioned by Christie’s in London, the largest auction house in the world.

In the letter, Tolkien rejoices that his correspondent “became a Catholic,” while lamenting difficult times for Catholicism. Given the tone of his words and the date, 1969, it easy to understand that Tolkien refers to the so-called “post-Council” period, or the years that followed the Second Vatican Ecumenical Council of the Catholic church (1962–1965). In fact, after the Council, there were theologians and pastors who, favoring what in 2005 Pope Benedict XVI defined “a hermeneutic of discontinuity and rupture” in relation to the Catholic Tradition and Papal teachings, brought scandal and unrest in the church. Tolkien always sided with “the ‘hermeneutic of reform’,” or “renewal in the continuity of the one subject-Church which the Lord has given to us,” to use again Benedict XVI’s words. In his published correspondence, his position is unequivocal. In his 1969 letter auctioned by Christie’s, he makes again clear “that the powers of darkness (Gates of Hell) shall not prevail” against the “recognized and ordered institution (ecclesia) loyal to the See of Peter,” as per the promise of Jesus in the Gospels, while his flock may indeed suffer from turmoil.

In the letter, Tolkien rejoices that his correspondent “became a Catholic,” while lamenting difficult times for Catholicism. Given the tone of his words and the date, 1969, it easy to understand that Tolkien refers to the so-called “post-Council” period, or the years that followed the Second Vatican Ecumenical Council of the Catholic church (1962–1965). In fact, after the Council, there were theologians and pastors who, favoring what in 2005 Pope Benedict XVI defined “a hermeneutic of discontinuity and rupture” in relation to the Catholic Tradition and Papal teachings, brought scandal and unrest in the church. Tolkien always sided with “the ‘hermeneutic of reform’,” or “renewal in the continuity of the one subject-Church which the Lord has given to us,” to use again Benedict XVI’s words. In his published correspondence, his position is unequivocal. In his 1969 letter auctioned by Christie’s, he makes again clear “that the powers of darkness (Gates of Hell) shall not prevail” against the “recognized and ordered institution (ecclesia) loyal to the See of Peter,” as per the promise of Jesus in the Gospels, while his flock may indeed suffer from turmoil.

Writing to Bell, Tolkien takes also the opportunity—as he often does in his letters—to pay a devout tribute to his “young, beautiful, and gifted mother,” Mabel Suffield Tolkien (1870–1904), for bringing him “as a small boy […] ‘out of the Land of Egypt’,” and dying “in a few years, largely owing to the poverty and griefs that followed her conversion.” In fact, a widow at the age of 26 in 1896, Mabel raised J.R.R. Tolkien and his younger brother, Hilary Arthur R. Tolkien (1894–1976), amongst rapidly increasing difficulties after she converted to Roman Catholicism. Passing also through High Church Anglicanism, Mabel was received into the Catholic Church in June 1900 with her two children and her sister, Edith Mary “May” Suffield Incledon (1865–1936).

At this point, her sister May’s husband, a fierce adversary of Catholicism, stopped his financial aid to the widow—and forced his own wife May to become a lapsed Catholic. The situation precipitated when even the Suffield family, many members of which were Baptists and strongly opposed Catholicism, denied assistance to Mabel and the boys, and Tolkien’s mother fell ill to diabetes. With no money to buy adequate medicines and a household to manage, Mabel eventually died, leaving her sons to the care of Father Francis Xavier Morgan (1857–1935), a Roman Catholic priest in the Oratory of Birmingham.

In his 1969 letter, Tolkien comments all that with a laconic “the spirit of Ian Paisley was then almost normal.” He of course refers to Ian Paisley, Baron Bannside (1926–2014), the Protestant evangelical minister who founded the Free Presbyterian Church of Ulster, was the leader of the Democratic Unionist Party, and the First Minister of Northern Ireland from 2007 to 2008. Paisley was in fact famous as a staunch anti-Catholic agitator.

In his 1969 letter, Tolkien comments all that with a laconic “the spirit of Ian Paisley was then almost normal.” He of course refers to Ian Paisley, Baron Bannside (1926–2014), the Protestant evangelical minister who founded the Free Presbyterian Church of Ulster, was the leader of the Democratic Unionist Party, and the First Minister of Northern Ireland from 2007 to 2008. Paisley was in fact famous as a staunch anti-Catholic agitator.

Further reflecting on the sea of troubles that Catholicism had in those years to sail in, and on the Gospels’ promise of the final victory of truth, in his letter to Bell Tolkien importantly adds: “Not, of course, that the free grace of God is withheld from any individual as such.” He cites the examples of C.S. Lewis (1898–1963), a quite different son of Ulster in comparison to Paisley.

Ross Wilson, statue of C.S. Lewis in Belfast, Northern Ireland. Credits.

Lewis was and author, literary critic, fine connoisseur of the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, and lay Anglican theologian born in Belfast, Northern Ireland. The Anglican Lewis and the Roman Catholic Tolkien became excellent friends, and the cornerstone of the informal literary club “The Inklings” in Oxford, which Carpenter described in a classic book first published in 1978, and American scholars of religion Philip and Carol Zaleski further dealt with in 2016. Lewis went from atheism to theism in 1929, then finally to Christianity in 1931, also thanks to J.R.R. Tolkien and their common friend, Oxford University academician Hugo Dyson (1896–1975). He remained an Anglican for all his life, to a certain disappointment of Tolkien, who wished, and almost expected, that Lewis could become a Roman Catholic.

Lewis was and author, literary critic, fine connoisseur of the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, and lay Anglican theologian born in Belfast, Northern Ireland. The Anglican Lewis and the Roman Catholic Tolkien became excellent friends, and the cornerstone of the informal literary club “The Inklings” in Oxford, which Carpenter described in a classic book first published in 1978, and American scholars of religion Philip and Carol Zaleski further dealt with in 2016. Lewis went from atheism to theism in 1929, then finally to Christianity in 1931, also thanks to J.R.R. Tolkien and their common friend, Oxford University academician Hugo Dyson (1896–1975). He remained an Anglican for all his life, to a certain disappointment of Tolkien, who wished, and almost expected, that Lewis could become a Roman Catholic.

But Lewis was a strong advocate of what he called “Mere Christianity,” a position consistent with the informal movement that, especially in the English-speaking world, search for, or aspire to, a shared “basic orthodoxy” among different brands of Christians, aimed at retaining a non-negotiable loyalty to a set of fundamental doctrinal and moral principles for the sake of preserving the authenticity of the Christian message.

But Lewis was a strong advocate of what he called “Mere Christianity,” a position consistent with the informal movement that, especially in the English-speaking world, search for, or aspire to, a shared “basic orthodoxy” among different brands of Christians, aimed at retaining a non-negotiable loyalty to a set of fundamental doctrinal and moral principles for the sake of preserving the authenticity of the Christian message.

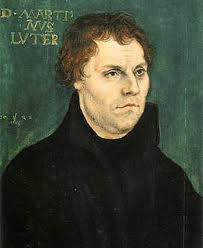

“A notable case was that of my dear friend C. S. Lewis,” Tolkien writes of his mate in his 1969 letter, “who arrived by degrees at a completely ‘Catholic’ position with regard to Our Lord, and especially to the Blessed Sacrament (in which at any rate he declared that our church was right).” Of course, the accent on the Blessed Sacrament is quite notable. The nature of the Eucharist was in fact one of the key points at the Reformation. Martin Luther (1483–1546), the initiator of Protestantism, advocated “consubstantiation”: this theological position holds that the substance of the bread and wine remain present in the Eucharist alongside the substance of the body and blood of Christ. Catholicism considers this unacceptable, affirming “transubstantiation”: in the Eucharist the substance of bread and wine change in the substance of the body and blood of Christ, while retaining their external characteristics only.

Further reformers denied even Luther’ position and Luther strongly criticized them, but in later centuries many Reformed and Anglican Christians came to see things differently. This writer still struggles trying to understand some High Church Anglican theologians he once discussed the topic with, who wished to explain to him that they believe in transubstantiation, implying however, they said, “not a Thomist theological jargon, but an Augustinian one.” Tolkien would have had much to add to that.

Further reformers denied even Luther’ position and Luther strongly criticized them, but in later centuries many Reformed and Anglican Christians came to see things differently. This writer still struggles trying to understand some High Church Anglican theologians he once discussed the topic with, who wished to explain to him that they believe in transubstantiation, implying however, they said, “not a Thomist theological jargon, but an Augustinian one.” Tolkien would have had much to add to that.

Lewis, Tolkien observed, “was in fact Pope in his own individual Church.” It is an ironic remark but it contains a poignant truth. Lewis was and is one of the ultimate authorities on the “Mere Christianity” movement, which seems to have many direct and indirect disciples. “And I am sure God accepted him as that,” Tolkien wrote, invoking God’s mercy upon the great friend who had passed away four years before, who had remained “hostile to the R.C. Church and never I think ever attended to Our Lady.”

Walter Hooper. From Twitter.

This writer had a few chances to discuss this topics and Lewis’s “implicit Catholicism” with the later Walter Hooper (1931–2020), an American who once was the writer’s personal secretary and then became the literary advisor of the Lewis’ estate. Hooper was an ordained Anglican priest since 1965 and became a Catholic in 1988. He was also a notable expert on the relationship between Lewis and Tolkien.

This writer had a few chances to discuss this topics and Lewis’s “implicit Catholicism” with the later Walter Hooper (1931–2020), an American who once was the writer’s personal secretary and then became the literary advisor of the Lewis’ estate. Hooper was an ordained Anglican priest since 1965 and became a Catholic in 1988. He was also a notable expert on the relationship between Lewis and Tolkien.

It is nice to underline this original contribution to a great spiritual exigence of our secular age on the very 50th anniversary of Tolkien’s death and in light of November 22’s 60th anniversary of the death of Lewis.