Dal sito First Things 16 Gennaio 2018

Dal sito First Things 16 Gennaio 2018

Questo è il secondo di una serie di riflessioni del cardinal Müller su questioni di importante attualità nella vita della Chiesa.

del Cardinale Gerhard Müller

Come si riferiscono il Magistero del Papa e la Tradizione della Chiesa? Quando il papa interpreta le parole di Gesù deve essere in continuità con la Tradizione e il Magistero precedente, compreso quello dei papi più recenti? O è piuttosto la Tradizione della Chiesa che deve essere reinterpretata alla luce delle nuove parole del papa? Cosa succede se ci sono contraddizioni?

Per rispondere a queste domande, sembra opportuno iniziare con un’importante lettera apostolica che Papa Pio IX ha inviato all’episcopato tedesco il 4 marzo 1875. Nella sua lettera il papa ha spiegato che i vescovi tedeschi avevano interpretato il dogma dell’ infallibilità del papa e del primato petrino in perfetta armonia con le definizioni del Concilio Vaticano I.

Ciò che aveva causato la lettera del papa era il dispaccio circolare del cancelliere tedesco Bismarck che ha interpretato in modo grave questo dogma per giustificare la brutale persecuzione dei cattolici tedeschi nel cosiddetto Kulturkampf, o “guerra culturale”. Secondo Pio IX, nella loro risposta alla provocazione di Bismarck i vescovi tedeschi hanno mostrato chiaramente «che non c’è assolutamente nulla nelle definizioni attaccate di nuovo e che nulla cambia riguardo ai nostri rapporti con i governi civili o che può offrire qualsiasi scusa per persistere nella persecuzione della Chiesa».

Cardinale Gerhard Müller

Certamente, per apprezzare gli eventi, bisogna essere consapevoli dei presupposti culturali da cui hanno operato Bismarck e i suoi “guerrieri della cultura” liberali. Sebbene avessero per lo più abbandonato il contenuto religioso della Riforma protestante che aveva segnato il loro paese, avevano ampiamente sostenuto i pregiudizi contro la Chiesa cattolica. Secondo la loro mente, l’ufficio di insegnamento esercitato dal papa e dai consigli della Chiesa rivendicava un’autorità più alta della stessa Parola di Dio. Non solo il magistero ecclesiale ostacolava l’immediata relazione del credente con Dio, ma si erigeva come elemento estraneo che si frapponeva tra i cittadini e lo stato – uno stato, per essere precisi, che nel caso della Prussia alla fine del diciannovesimo secolo attribuiva a se stessa un’autorità totale, distaccata anche dalla legge morale naturale.

Bismarck e i suoi sostenitori erano convinti che l’autorità del papa si estendesse all’invenzione e all’istituzione arbitrarie di dottrine e pratiche su tutta la Chiesa, compresi i cittadini cattolici tedeschi, che sarebbero quindi tenuti ad aderire a questi sotto la minaccia della scomunica e della perdita della vita eterna. Contro questa caricatura del potere del papa, i vescovi tedeschi hanno sottolineato che “in tutti i punti essenziali la costituzione della Chiesa è basata su direttive divine, e quindi non è soggetta all’arbitrio umano”.

Per quanto riguarda loro, «l’opinione secondo cui il papa è “un sovrano assoluto a causa della sua infallibilità” si basa su una comprensione completamente falsa del dogma dell’infallibilità papale». Infatti, il Magistero del papa «è limitato ai contenuti della Sacra Scrittura e della tradizione e anche al dogmi precedentemente definiti dall’autorità didattica della Chiesa».

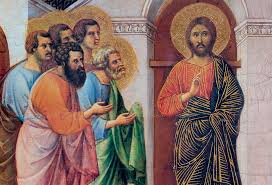

Il fatto è che l’ufficio di insegnamento tenuto dal papa e dai vescovi in unione con lui è un ministero al servizio della Parola di Dio, un Verbo che si è fatto carne in Gesù Cristo. Cristo è quindi l’unico Maestro (cfr Mt 23:10), che ci proclama “parole di vita eterna” (cfr Gv 6, 68). Rispetto a lui, Pietro, gli apostoli e tutti i battezzati sono fratelli e sorelle dell’unico Padre celeste.

Senza pregiudizio del fatto che tutti i credenti sono fratelli e sorelle, Gesù ha scelto alcuni tra i suoi molti discepoli per essere i suoi apostoli, dando loro l’autorità di insegnare e governare. Ha affidato loro «il messaggio della riconciliazione», così che ora agiscano nella persona stessa di Cristo per la salvezza del mondo (cfr 2 Cor 5, 19 s).

Il Signore risorto, al quale tutto il potere è dato in cielo e sulla terra, manda i suoi apostoli in tutto il mondo per fare discepoli di tutte le nazioni e battezzarli nel nome del Padre e del Figlio e dello Spirito Santo. Commissionando i suoi apostoli, Gesù commissiona anche i loro successori, cioè i vescovi, insieme al successore di Pietro, il papa, come loro capo. Il mandato che Cristo dà loro è di «insegnare loro ad osservare tutto ciò che vi ho comandato» (Mt 28,20). In questo modo chiarisce che il contenuto dell’insegnamento degli apostoli – il criterio della verità di ciò che stanno dicendo – è il suo insegnamento. La certezza della fede cristiana si basa in definitiva sul fatto che la parola umana degli apostoli e dei vescovi è la divina Parola di salvezza, non prodotta ma piuttosto testimoniata dal mediatore umano (cfr 1 2:13).

Il Signore risorto, al quale tutto il potere è dato in cielo e sulla terra, manda i suoi apostoli in tutto il mondo per fare discepoli di tutte le nazioni e battezzarli nel nome del Padre e del Figlio e dello Spirito Santo. Commissionando i suoi apostoli, Gesù commissiona anche i loro successori, cioè i vescovi, insieme al successore di Pietro, il papa, come loro capo. Il mandato che Cristo dà loro è di «insegnare loro ad osservare tutto ciò che vi ho comandato» (Mt 28,20). In questo modo chiarisce che il contenuto dell’insegnamento degli apostoli – il criterio della verità di ciò che stanno dicendo – è il suo insegnamento. La certezza della fede cristiana si basa in definitiva sul fatto che la parola umana degli apostoli e dei vescovi è la divina Parola di salvezza, non prodotta ma piuttosto testimoniata dal mediatore umano (cfr 1 2:13).

Fin dai tempi di Ireneo di Lione nel secondo secolo, è stata stabilita una terminologia secondo la quale il contenuto della rivelazione si trova nella Sacra Scrittura e nella Tradizione apostolica. Questa rivelazione è autorevolmente proclamata dal magistero ecclesiastico costituito dal papa e dai vescovi in unione con lui. In contrasto con il principio di sola scriptura – la sola Bibbia – che la Riforma ha avuto, il Concilio di Trento sottolinea che appartiene alla Santa Madre Chiesa per giudicare il vero significato e l’interpretazione della Sacra Scrittura – e nessuno può osare interpretare la Scrittura in modo contrario al consenso unanime dei Padri.

Il Concilio Vaticano II riprende questo modo fondamentale di interpretare la fede cattolica e ne trae la conclusione: «Questo Magistero non è superiore alla Parola di Dio, ma è il suo servitore. Insegna solo ciò che è stato tramandato. Al comando divino e con l’aiuto dello Spirito Santo, ascolta questo devoto, lo custodisce con dedizione e lo espone fedelmente. Tutto ciò che propone per credere come divinamente rivelato è tratto da questo singolo deposito di fede» (Dei Verbum, 10).

C’è accordo tra tutti i cristiani sul fatto che la Sacra Scrittura è la Parola di Dio. Ma dal momento che questa Parola è trasmessa nel linguaggio umano, non ha l’evidenza in se stessa che i protestanti vogliono attribuirle. Piuttosto, c’è bisogno di un’interpretazione umana da parte degli insegnanti della fede la cui autorità proviene dallo Spirito Santo. Verso coloro che ascoltano la Parola di Dio, questi insegnanti rappresentano l’autorità di Dio, facendo uso delle parole e delle decisioni umane.

Il compito di autorevole insegnamento e governo non può essere lasciato solo al singolo credente, che nella sua coscienza arriva ad accettare una certa verità. Dopo tutto, la rivelazione è stata affidata alla Chiesa nel suo insieme. Pertanto, il Magistero è una parte essenziale della missione della Chiesa. Solo con l’aiuto del magistero vivente del papa e dei vescovi la Parola di Dio può essere trasmessa nella sua integrità ai fedeli e a tutto il popolo di tutti i tempi e luoghi.

Nel nostro credo professiamo la nostra fede usando le parole umane. Queste parole sono soggette ad un certo cambiamento, per quanto riguarda la modalità di espressione. Ciò è possibile ed effettivamente necessario, poiché, come afferma chiaramente san Tommaso, «l’atto del credente non termina in una proposizione, ma in una cosa» (STh II-II 1,2, ad 2).

Nel nostro credo professiamo la nostra fede usando le parole umane. Queste parole sono soggette ad un certo cambiamento, per quanto riguarda la modalità di espressione. Ciò è possibile ed effettivamente necessario, poiché, come afferma chiaramente san Tommaso, «l’atto del credente non termina in una proposizione, ma in una cosa» (STh II-II 1,2, ad 2).

Nella misura in cui l’insegnamento degli apostoli – e quindi l’insegnamento della Chiesa – è la Parola di Dio nelle parole degli esseri umani, la Parola di Dio prende forma e si sviluppa nella coscienza della sua fede nella Chiesa, in modo abbastanza analogo al modo in cui ciascuno dei fedeli subisce uno sviluppo spirituale e storico sotto la guida dello Spirito Santo.

Certo, la missione dello Spirito Santo non consiste nel creare nuove dottrine, ma nel rendere presente nella Chiesa la pienezza della rivelazione di Gesù Cristo (cfr Gv 16,13).

Nella misura in cui il papa, in quanto capo del collegio dei vescovi, è il principio dell’unità della Chiesa nella verità, ha la missione di preservare la verità della rivelazione e di stabilire nuove formulazioni concettuali del credo (il “simbolo”). dove necessario. Nel fare ciò, non può aggiungere nulla alla rivelazione dataci nella Scrittura e nella Tradizione, né può modificare il contenuto delle precedenti definizioni dogmatiche.

Ma per preservare l’unità della Chiesa nella fede, in determinate circostanze ha il diritto e il dovere di dare una nuova formulazione al credo (nova editio symboli). Tommaso d’Aquino spiega: «La verità della fede è sufficientemente esplicita nell’insegnamento di Cristo e degli apostoli. Ma dal momento che, secondo 2 Pt. 3:16, alcuni uomini sono così malvagi da alterare l’insegnamento apostolico e le altre dottrine e le Scritture alla loro stessa distruzione, era necessario, col passare del tempo, esprimere la fede in modo più esplicito contro gli errori sorti» (STh II- II, 1, 10 ad 1, corsivo aggiunto).

Per questo compito, il magistero attinge l’apprezzamento soprannaturale della fede (sensus fidei) data dallo Spirito Santo a tutto il Popolo di Dio sotto la guida dei vescovi (cfr Lumen Gentium 12). Ma attira anche teologi. Senza il lavoro teologico preparatorio di sant’Atanasio e dei padri cappadoci, non ci sarebbe stato il Credo niceno né la sua difesa e le sue specifiche nei consigli successivi. Allo stesso modo, i decreti del Concilio di Trento non sarebbero stati possibili senza il lavoro preparatorio dei teologi più istruiti di quel tempo.

È vero che per il Concilio Vaticano II la trasmissione storica e fedele della rivelazione ha le sue basi nel carisma dell’infallibilità, che è propria del papa e dei consigli ecumenici. Allo stesso tempo, il Vaticano II non manca di aggiungere: «Il Romano Pontefice e i vescovi, in ragione del loro ufficio e della gravità della questione, si applicano con zelo all’opera di indagare con ogni mezzo adeguato in questa rivelazione e di dare la giusta espressione ai suoi contenuti; tuttavia, essi non ammettono alcuna nuova rivelazione pubblica relativa al deposito divino della fede » (Lumen Gentium 25).

Certamente, un cattolico, non può ignorare la dottrina sviluppata dalla Chiesa per frequentare unicamente la dottrina della Scrittura apparentemente pura. La parabola del figliol prodigo, ad esempio, non impartisce una istruzione catechetica sul sacramento del pentimento nella sua materia (pentimento, confessione, soddisfazione) e forma (assoluzione del sacerdote).

Se si guardasse la Scrittura da sola, si potrebbe quindi concludere che, dal momento che il figlio non si è effettivamente preoccupato di confessare i suoi peccati, non è nemmeno necessario farlo. Tuttavia, contrastare la Scrittura contro la Chiesa in questo modo significherebbe ignorare completamente le parole di Cristo, che ha affidato agli apostoli – con Pietro come loro capo – la conservazione fedele dell’intero deposito di fede.

Cristo ha messo il papa «a capo degli altri apostoli, e in lui ha costituito una sorgente e un fondamento duraturi e visibili dell’unità di fede e di comunione» (Lumen Gentium 18). Ora, la pienezza dell’autorità apostolica non implica una pienezza illimitata di potere nel senso secolare. Piuttosto, questo potere è strettamente limitato dal suo scopo: è al servizio della preservazione dell’unità della Chiesa nella sua fede nel Figlio di Dio che è venuto nella «pienezza dei tempi» (Gal 4: 4-6).

Cristo ha messo il papa «a capo degli altri apostoli, e in lui ha costituito una sorgente e un fondamento duraturi e visibili dell’unità di fede e di comunione» (Lumen Gentium 18). Ora, la pienezza dell’autorità apostolica non implica una pienezza illimitata di potere nel senso secolare. Piuttosto, questo potere è strettamente limitato dal suo scopo: è al servizio della preservazione dell’unità della Chiesa nella sua fede nel Figlio di Dio che è venuto nella «pienezza dei tempi» (Gal 4: 4-6).

L’autorità del papa è strettamente legata alla rivelazione; anzi, deriva dalla rivelazione. È solo attraverso il potere di Dio che Pietro è in grado di preservare l’intera Chiesa nella fedeltà a Cristo, anche quando Satana la scuote e la setaccia, in modo che il grano possa essere rimosso dalla pula. Come dice Gesù, «Ma ho pregato affinché la tua stessa fede non fallisse» (Luca 22:32). Nel suo magistero supremo, il papa unisce la Chiesa intera e tutti i suoi vescovi nella stessa confessione: «Tu sei il Cristo, il Figlio del Dio vivente» (Mt 16,16). Ed è proprio in questa confessione che egli è la roccia su cui il Signore Gesù continua a costruire la sua Chiesa fino alla fine del mondo. È quindi chiaro che le parole del papa sono al servizio di tutta la Tradizione della Chiesa, e non viceversa.

Quanto detto sopra si riferisce all’insegnamento della Chiesa, ma anche all’amministrazione dei suoi mezzi di grazia nei sacramenti. Nel suo decreto sulla Santa Comunione, il Concilio di Trento dichiara che la Chiesa ha il potere di determinare o modificare i riti esterni dei sacramenti. Allo stesso tempo, il Concilio nega che la Chiesa abbia il diritto o la capacità di interferire con l’essenza dei sacramenti, insistendo sul fatto che «la loro sostanza è preservata».

Quando il Concilio di Trento definisce che ci sono tre atti del penitente che formano parte del sacramento della penitenza (pentimento con la decisione di non peccare di nuovo, confessione e soddisfazione), quindi anche i papi e i vescovi delle epoche successive sono vincolati da questa dichiarazione. Non sono liberi di concedere l’assoluzione sacramentale per i peccati, o di autorizzare i loro sacerdoti a farlo, quando i penitenti in realtà non mostrano segni di pentimento o dove rifiutano esplicitamente la decisione di non peccare di nuovo.

Nessun essere umano può annullare la contraddizione interiore tra l’effetto del sacramento – cioè la nuova comunione della vita con Cristo nella fede, nella speranza e nell’amore – e la disposizione inadeguata del penitente. Neanche il papa o un sinodo possono farlo, perché mancano dell’autorità, né potrebbero mai ricevere tale autorità, perché Dio non chiede mai agli esseri umani di fare qualcosa che sia al contempo contraddittorio e contrario a Dio stesso.

Bisogna tenere a mente che le dichiarazioni dottrinali hanno vari gradi di autorità. Richiedono gradi diversi di consenso, come espresso dalle cosiddette “note teologiche”. L’accettazione di un insegnamento con “fede divina e cattolica” è richiesta solo per le definizioni dogmatiche. È anche chiaro che il papa o i vescovi non devono mai chiedere a nessuno di agire o insegnare contro la legge morale naturale.

L’obbedienza dei fedeli verso i loro superiori ecclesiali non è quindi un’assoluta obbedienza, e il superiore non può esigere un’obbedienza assoluta, perché sia il superiore che quelli affidati alla sua autorità sono fratelli e sorelle dello stesso Padre, e sono discepoli del stesso maestro. Pertanto, è più difficile insegnare che imparare, perché l’insegnamento è associato a una maggiore responsabilità di fronte a Dio. L’affermazione «Dobbiamo obbedire a Dio piuttosto che agli uomini” (Atti 5:29) ha la sua validità anche e soprattutto nella Chiesa.

Contro il principio di assoluta obbedienza prevalente nello stato militare prussiano, i vescovi tedeschi hanno insistito prima di Bismarck: «Non è certamente la Chiesa cattolica che ha abbracciato il principio immorale e dispotico che il comando di un superiore libera incondizionatamente da ogni responsabilità personale».

Contro il principio di assoluta obbedienza prevalente nello stato militare prussiano, i vescovi tedeschi hanno insistito prima di Bismarck: «Non è certamente la Chiesa cattolica che ha abbracciato il principio immorale e dispotico che il comando di un superiore libera incondizionatamente da ogni responsabilità personale».

Quando le opinioni private o le limitazioni spirituali e morali entrano nell’esercizio dell’autorità ecclesiastica, allora è necessaria una critica sobria e obiettiva e una correzione personale, specialmente dai fratelli nell’ufficio episcopale. Tommaso d’Aquino non sarà sospettato di relativizzare il primato petrino e la virtù dell’obbedienza. Ancora più chiaro è il modo in cui interpreta l’episodio di Antiochia, che culmina nella pubblica correzione di Paolo su Pietro (Gal 2:11).

Secondo Tommaso d’Aquino, l’evento ci insegna che in certe circostanze un apostolo può avere il diritto e persino il dovere di correggere un altro apostolo in modo fraterno, che anche un inferiore può avere il diritto e il dovere di criticare il superiore (cfr. Galati, Cap. II, lezione 3). Ciò non significa che si possa ridurre il magistero a un’opinione privata, in modo da dispensarsi dal potere vincolante dell’insegnamento autentico e definito della Chiesa (cfr Lumen gentium 37). Significa solo che bisogna capire bene il significato preciso dell’autorità nella Chiesa in generale e il ruolo del ministero di Pietro in particolare. Ciò è particolarmente vero quando il conflitto non sorge tra l’insegnamento del papa e la propria visione, ma tra l’insegnamento del papa e un insegnamento di papi precedenti che è in accordo con la tradizione ininterrotta della Chiesa.

Come ha spiegato Papa Benedetto XVI durante la Messa in occasione della sua presa di possesso della Cattedra del Vescovo di Roma, il 7 maggio 2005, «Il potere che Cristo ha conferito a Pietro e ai suoi Successori è, in un senso assoluto, un mandato per servire . Il potere di insegnare nella Chiesa implica un impegno al servizio dell’obbedienza alla fede».

Continua: «Il papa non è un monarca assoluto i cui pensieri e desideri sono legge. Al contrario: il ministero del papa è una garanzia di obbedienza a Cristo e alla sua Parola. Non deve proclamare le proprie idee, ma piuttosto legare costantemente se stesso e la Chiesa all’obbedienza alla Parola di Dio, di fronte a ogni tentativo di adattarlo o di annaffiarlo, e ogni forma di opportunismo».

(cardinale Gerhard Ludwig Müller ex prefetto della Congregazione per la dottrina della fede)[traduzione a cura di Rassegna Stampa]

_________________________

BY WHAT AUTHORITY?

ON THE TEACHING OFFICE OF THE POPE

This is the second in a series of reflections by Cardinal Müller on questions of present importance in the life of the Church. The first, on subjectivity, culpability, and confession, may be found here.

By Gerhard Cardinal Müller

How do the pope’s Magisterium and the Tradition of the Church relate? When he interprets the words of Jesus, must the pope be in continuity with the Tradition and the previous Magisterium, including that of the most recent popes? Or is it rather the Church’s Tradition that has to be reinterpreted in the light of the pope’s new words? What if there are contradictions?

In order to answer these questions, it seems appropriate to begin with an important Apostolic Letter that Pope Pius IX sent to the German episcopate on March 4, 1875. In his letter, the pope explained that the German bishops had interpreted the dogma of the papal infallibility and Petrine primacy in perfect harmony with the definitions of the First Vatican Council.

What had occasioned the pope’s letter was the German chancellor Bismarck’s circular dispatch that gravely misinterpreted this dogma in order to justify the brutal persecution of German Catholics in the so-called Kulturkampf, or “culture-war.” According to Pius IX, in their response to Bismarck’s provocation the German bishops clearly showed “that there is absolutely nothing in the attacked definitions that is new or that changes anything at all with regard to our relations with civil governments or that can offer any excuse to persist in the persecution of the Church”

Of course, to appreciate the events, one must be aware of the cultural presuppositions from which Bismarck and his liberal “culture warriors” operated. Although they had mostly abandoned the religious content of the Protestant Reformation that had marked their country, they had widely maintained the related prejudices against the Catholic Church. To their mind, the teaching office exercised by the pope and by the Church’s councils claimed a higher authority than the Word of God itself. Not only did the ecclesial magisterium obstruct the immediate relationship of the believer to God, but it set itself up as a foreign element that stood between the citizens and the state—a state, to be sure, that in the case of the late-nineteenth-century Prussia ascribed to itself a total authority, detached even from the natural moral law.

Of course, to appreciate the events, one must be aware of the cultural presuppositions from which Bismarck and his liberal “culture warriors” operated. Although they had mostly abandoned the religious content of the Protestant Reformation that had marked their country, they had widely maintained the related prejudices against the Catholic Church. To their mind, the teaching office exercised by the pope and by the Church’s councils claimed a higher authority than the Word of God itself. Not only did the ecclesial magisterium obstruct the immediate relationship of the believer to God, but it set itself up as a foreign element that stood between the citizens and the state—a state, to be sure, that in the case of the late-nineteenth-century Prussia ascribed to itself a total authority, detached even from the natural moral law.

Bismarck and his supporters were convinced that the pope’s authority extended to arbitrarily inventing and then imposing doctrines and practices on the whole Church, including German Catholic citizens, who would then be bound to adhere to these under the threat of excommunication and loss of eternal life. Against this total caricature of the pope’s fullness of power, the German bishops emphasized that “in all essential points the constitution of the Church is based on divine directives, and therefore it is not subject to human arbitrariness.” As to them, “the opinion according to which the pope is ‘an absolute sovereign because of his infallibility’ is based on a completely false understanding of the dogma of papal infallibility.” Indeed, the pope’s Magisterium “is restricted to the contents of Holy Scripture and tradition and also to the dogmas previously defined by the teaching authority of the Church.”

The fact is that the teaching office held by the pope and by the bishops in union with him is a ministry in the service of the Word of God, a Word that became flesh in Jesus Christ. Christ is thus the only Teacher (cf. Mt 23:10), who proclaims to us the “words of eternal life” (cf. Jn 6:68). With respect to him, Peter, the apostles, and all the baptized are brothers and sisters of the one heavenly Father.

Without prejudice to the fact that all believers are brothers and sisters, Jesus has chosen some from among his many disciples to be his apostles, giving them the authority to teach and govern. He entrusted to them “the message of reconciliation,” so that now they are acting in the very person of Christ for the salvation of the world (cf. 2 Cor 5:19f). The risen Lord, to whom all power is given in heaven and on earth, sends his apostles into all the world to make disciples of all nations and to baptize them in the name of the Father and the Son and the Holy Spirit.

Commissioning his apostles, Jesus also commissions their successors, that is, the bishops, together with the successor of Peter, the pope, as their head. The mandate Christ gives them is to “teach them to observe all that I have commanded you” (Mt 28:20). In this way he makes it clear that the content of the apostles’ teaching—the criterion of the truth of what they are saying—is his own teaching. The certainty of the Christian faith ultimately rests on the fact that the human word of the apostles and bishops is the divine Word of salvation, not produced but rather witnessed by the human mediator (cf. 1 Thess 2:13).

Since the time of Irenaeus of Lyon in the second century, a terminology has been firmly established according to which the content of revelation is found in Holy Scripture and in the Apostolic Tradition. This revelation is authoritatively proclaimed by the ecclesiastical magisterium consisting of the pope and the bishops in union with him. In contrast to the principle sola scriptura, the Bible alone, as the Reformation had it, the Council of Trent emphasizes that it belongs to Holy Mother Church “to judge the true meaning and interpretation of Holy Scripture—and . . . no one may dare to interpret the Scripture in a way contrary to the unanimous consensus of the Fathers.”

The Second Vatican Council takes up this fundamental way of interpreting the Catholic faith and concludes from it: “This Magisterium is not superior to the Word of God, but is its servant. It teaches only what has been handed on to it. At the divine command and with the help of the Holy Spirit, it listens to this devotedly, guards it with dedication and expounds it faithfully. All that it proposes for belief as being divinely revealed is drawn from this single deposit of faith” (Dei Verbum, n. 10).

There is agreement among all Christians that Holy Scripture is the Word of God. But since this Word is conveyed in human language, it does not have the evidence (quoad se—in itself) that the Protestants want to attribute to it. Rather, there is need for a human interpretation on the part of the teachers of the faith whose authority comes from the Holy Spirit. Toward those who hear the Word of God, these teachers represent God’s own authority, making use of human words and decisions (quoad nos—to us). The task of authoritative teaching and governing cannot be left solely to the individual believer who in his or her conscience comes to accept a certain truth. After all, revelation has been entrusted to the Church as a whole. Therefore, the Magisterium is an essential part of the Church’s mission. Only with the help of the living magisterium of the pope and the bishops can the Word of God be passed on in its integrity to the faithful and to all the people of all times and places.

There is agreement among all Christians that Holy Scripture is the Word of God. But since this Word is conveyed in human language, it does not have the evidence (quoad se—in itself) that the Protestants want to attribute to it. Rather, there is need for a human interpretation on the part of the teachers of the faith whose authority comes from the Holy Spirit. Toward those who hear the Word of God, these teachers represent God’s own authority, making use of human words and decisions (quoad nos—to us). The task of authoritative teaching and governing cannot be left solely to the individual believer who in his or her conscience comes to accept a certain truth. After all, revelation has been entrusted to the Church as a whole. Therefore, the Magisterium is an essential part of the Church’s mission. Only with the help of the living magisterium of the pope and the bishops can the Word of God be passed on in its integrity to the faithful and to all the people of all times and places.

In our creed we profess our faith by making use of human words. These words are subject to a certain change, as far as the mode of expression is concerned. This is possible and indeed necessary, since, as St. Thomas clearly states, “the act of the believer does not terminate in a proposition, but in a thing” (STh II-II 1,2, ad 2). Inasmuch as the teaching of the apostles—and thus the teaching of the Church—is the Word of God in the words of human beings, the Word of God takes shape and develops in the Church’s consciousness of her faith, quite analogously to the way each of the faithful undergoes a spiritual and historical development under the guidance of the Holy Spirit. To be sure, the mission of the Holy Spirit does not consist in creating new doctrines, but in making present in the Church the fullness of the revelation of Jesus Christ (cf. Jn 16:13).

Insofar as the pope, as the head of the college of bishops, is the principle of the Church’s unity in the truth, he has the mission both to preserve the truth of revelation and to establish new conceptual formulations of the creed (the “symbol”) where necessary. In doing so, he cannot add anything to the revelation given to us in Scripture and Tradition, nor can he change the content of previous dogmatic definitions. But in order to preserve the Church’s unity in the faith, under certain circumstances he has the right and duty to give a new formulation to the creed (nova editio symboli). Thomas Aquinas explains, “The truth of faith is sufficiently explicit in the teaching of Christ and the apostles. But since, according to 2 Pt. 3:16, some men are so evil-minded as to pervert the apostolic teaching and other doctrines and Scriptures to their own destruction, it was necessary as time went on to express the faith more explicitly against the errors which arose” (Sth II-II, 1, 10 ad 1, emphasis added).

For this task, the magisterium draws upon the supernatural appreciation of the faith (sensus fidei) given by the Holy Spirit to the whole People of God under the guidance of the bishops (cf. Lumen Gentium n. 12). But it also draws upon theologians. Without the theological preparatory work of St. Athanasius and the Cappadocian Fathers, there would not have been the Nicene Creed nor its defense and specification in the subsequent councils. Likewise, the decrees of the Council of Trent would not have been possible without the preparatory work of the most learned theologians of that time.

It is true that for the Second Vatican Council the faithful and complete historical transmission of revelation has its basis in the charism of infallibility, which is proper to the pope and to ecumenical councils. At the same time, Vatican II does not fail to add: “The Roman Pontiff and the bishops, by reason of their office and the seriousness of the matter, apply themselves with zeal to the work of inquiring by every suitable means into this revelation and of giving apt expression to its contents; they do not, however, admit any new public revelation as pertaining to the divine deposit of faith” (Lumen Gentium. n. 25).

It is true that for the Second Vatican Council the faithful and complete historical transmission of revelation has its basis in the charism of infallibility, which is proper to the pope and to ecumenical councils. At the same time, Vatican II does not fail to add: “The Roman Pontiff and the bishops, by reason of their office and the seriousness of the matter, apply themselves with zeal to the work of inquiring by every suitable means into this revelation and of giving apt expression to its contents; they do not, however, admit any new public revelation as pertaining to the divine deposit of faith” (Lumen Gentium. n. 25).

Of course, as a Catholic, one cannot ignore the developed doctrine of the Church in order to attend solely to the supposedly pure doctrine of Scripture. The parable of the prodigal son, for example, does not give a catechetical instruction on the sacrament of repentance in its matter (repentance, confession, satisfaction) and form (absolution by the priest). If one were to look at Scripture alone, one could then conclude that, since the son did not actually get around to confessing his sins, neither do we need to do so. However, opposing Scripture against the Church in this way would mean completely to ignore the words of Christ, who entrusted the apostles—with Peter as their head—with the faithful preservation of the entire deposit of faith.

Christ has put the pope “at the head of the other apostles, and in him he set up a lasting and visible source and foundation of the unity both of faith and of communion” (Lumen Gentium n. 18). Now, the fullness of apostolic authority does not imply an unlimited fullness of power in the secular sense. Rather, this power is strictly limited by its purpose: It stands at the service of the preservation of the Church’s unity in her faith in God’s Son who came in “the fullness of time” (Gal 4:4–6).

The pope’s authority is most closely tied to revelation; indeed, it derives from revelation. It is only through the power of God that Peter is able to preserve the whole Church in fidelity to Christ, even when Satan shakes and sifts her, so that the wheat may be removed from the chaff. As Jesus says, “But I have prayed that your own faith may not fail” (Luke 22:32). In his supreme magisterium, the pope unites the whole Church and all its bishops in the same confession: “You are the Christ, the Son of the living God” (Mt 16:16). And it is precisely in this confession that he is the rock on which the Lord Jesus continues to build his Church until the end of the world. It is, then, clear that the pope’s words are at the service of the whole Tradition of the Church, and not the other way around.

What has been said above refers to the teaching of the Church, but also to the administration of her means of grace in the sacraments. In its Decree on Holy Communion, the Council of Trent declares that the Church has the power to determine or modify the external rites of the sacraments. At the same time, the Council denies that the Church has the right or ability to interfere with the essence of the sacraments, insisting that “their substance is preserved.” When the Council of Trent defines that there are three acts of the penitent that form part of the sacrament of penance (repentance with the resolve not to sin again, confession, and satisfaction), then the popes and bishops of subsequent ages, too, are bound by this declaration.

They are not free to grant sacramental absolution for sins, or to authorize their priests to do so, when penitents do not actually show signs of repentance or where they explicitly reject the resolve not to sin again. No human being can undo the inner contradiction between the effect of the sacrament—that is, the new communion of life with Christ in faith, hope, and love—and the penitent’s inadequate disposition. Not even the pope or a council can do so, because they lack the authority, nor could they ever receive such authority, because God never asks human beings to do something that is both self-contradictory and contrary to God himself.

They are not free to grant sacramental absolution for sins, or to authorize their priests to do so, when penitents do not actually show signs of repentance or where they explicitly reject the resolve not to sin again. No human being can undo the inner contradiction between the effect of the sacrament—that is, the new communion of life with Christ in faith, hope, and love—and the penitent’s inadequate disposition. Not even the pope or a council can do so, because they lack the authority, nor could they ever receive such authority, because God never asks human beings to do something that is both self-contradictory and contrary to God himself.

One must keep in mind that doctrinal statements have varying degrees of authority. They require varying degrees of consent, as expressed by the so-called “theological notes.” The acceptance of a teaching with “divine and Catholic faith” is required only for dogmatic definitions. It is also clear that the pope or bishops must never ask anyone to act or teach against the natural moral law. The obedience of the faithful toward their ecclesial superiors is therefore no absolute obedience, and the superior cannot demand absolute obedience, because both the superior and those entrusted to his or her authority are brothers and sisters of the same Father, and they are disciples of the same Master.

Therefore, it is harder to teach than to learn, because teaching is associated with a greater responsibility before God. The affirmation “We must obey God rather than men” (Acts 5:29) has its validity also and especially in the Church. Against the principle of absolute obedience prevailing in the Prussian military state, the German bishops insisted before Bismarck: “It is certainly not the Catholic Church that has embraced the immoral and despotic principle that the command of a superior frees one unconditionally from all personal responsibility.”

When private opinions or spiritual and moral limitations enter into the exercise of ecclesiastical authority, then sober and objective criticism as well as personal correction are called for, especially from the brothers in the episcopal office. Thomas Aquinas will not be suspected of relativizing Petrine primacy and the virtue of obedience. All the more elucidating is the way in which he interprets the incident in Antioch, culminating in Paul’s public correction of Peter (Gal 2:11). According to Aquinas, the event teaches us that under certain circumstances an apostle may have the right and even the duty to correct another apostle in a fraternal way, that even an inferior may have the right and duty to criticize the superior (cf. Commentary on Galatians, Chap. II, lecture 3).

This does not mean that one may reduce the magisterium to a private opinion, so as to dispense oneself from the binding power of the authentic and defined teaching of the Church (cf. Lumen Gentium 37). It only means that one must understand well the precise meaning of authority in the Church in general and the role of Peter’s ministry in particular. This is especially true when the conflict does not arise between the pope’s teaching and one’s own vision, but between the pope’s teaching and a teaching of previous popes that is in accordance with the uninterrupted tradition of the Church.

This does not mean that one may reduce the magisterium to a private opinion, so as to dispense oneself from the binding power of the authentic and defined teaching of the Church (cf. Lumen Gentium 37). It only means that one must understand well the precise meaning of authority in the Church in general and the role of Peter’s ministry in particular. This is especially true when the conflict does not arise between the pope’s teaching and one’s own vision, but between the pope’s teaching and a teaching of previous popes that is in accordance with the uninterrupted tradition of the Church.

As Pope Benedict XVI explained during the Mass on the occasion of his taking possession of the Chair of the Bishop of Rome on 7 May 2005, “The power that Christ conferred upon Peter and his Successors is, in an absolute sense, a mandate to serve. The power of teaching in the Church involves a commitment to the service of obedience to the faith.” He continues, “The pope is not an absolute monarch whose thoughts and desires are law. On the contrary: The pope’s ministry is a guarantee of obedience to Christ and to his Word. He must not proclaim his own ideas, but rather constantly bind himself and the Church to obedience to God’s Word, in the face of every attempt to adapt it or water it down, and every form of opportunism.”

Gerhard Ludwig Cardinal Müller is former prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith.